Cruel Inversions

by Sean Nelson

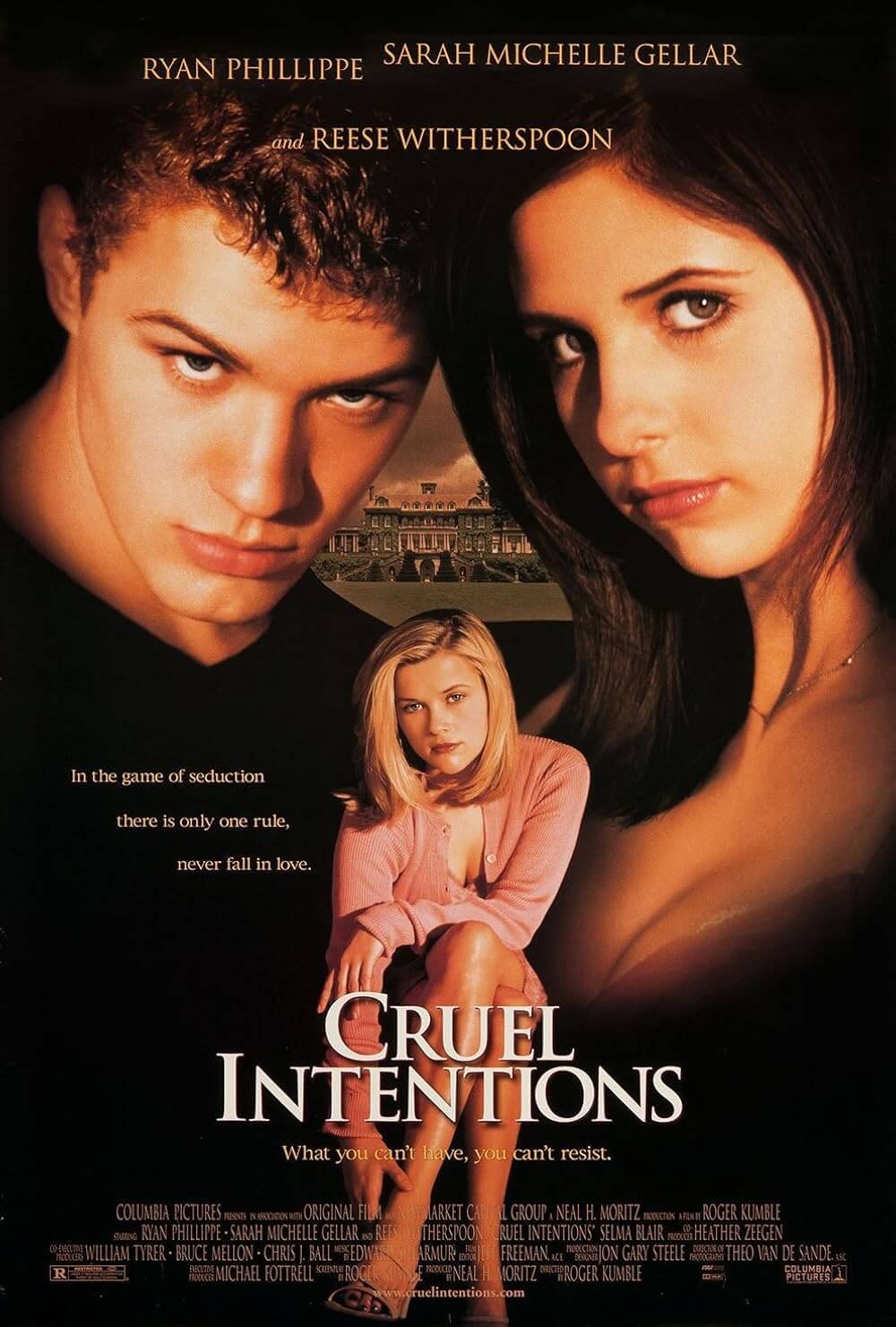

A call arrived that the producers of a new film called Cruel Inventions, which would be a teen transliteration of Stephen Frears’s and Christopher Hampton’s Dangerous Liaisons, wanted to use a Harvey Danger song for the opening title theme.

This was big news for several reasons: 1) The song was not “Flagpole Sitta.” It was, in fact, an unreleased song we had always called “Pity and Fear.” This was promising.

2) The opening title theme song of a film was a big opportunity no matter what. I mean, even if it’s not Christopher Cross singing “Arthur’s Theme,” or Simon and Garfunkel doing “The Sound of Silence” as Benjamin begins his descent into Los Angeles, a song that opens the film has a pretty strong role. (Also, the money would be good, something like $100,000—which of course, we wouldn’t actually see any of, but it would go some distance toward earning out our publishing advance.)

3) Ever since I first saw it in the theater, I’d had a powerful love for Dangerous Liaisons (and no, not just because of the telltale Uma Thurman scene). Thanks mostly to the performance of John Malkovich as the Vicomte de Valmont and the impeccable production design, its kinky, Jacobean sensibility rang my bell.

I was in San Francisco when the offer came and I asked if I could see the film. A screening was arranged the next day at the offices of American Zoetrope, Francis Ford Coppola’s production company. This, frankly, was the most exciting part so far: A private screening of a major new studio film at Zoetrope so I could decide if we should let them use a two-year-old b-side as its theme song. Surely, even I could admit this was a rockstar situation.

The movie was… I mean, it wasn’t terrible.

The movies we had licensed “Flagpole” to—Disturbing Behavior and EDTV, for example—they were terrible. This one was… well, it had a certain integrity. Cruel Inventions was a sex melodrama for teenagers, and better than many exponents of that genre. It may have taken credit for being smarter than it was, but who among us can’t say the same?

Anyway, the original play was a bit of high lowbrow and so this new teen version was in keeping with its fundamental nature. Plus, the actors—(fellow Nashvillian) Reese Witherspoon, Ryan Phillipe, and Selma Blair—were pretty good. Whatever the case, it also seemed like it had every chance of being a reasonably big hit and thereby extending our accidental career by another few months, and with a different song, amen. I conferred with the lads and we said yes. All that was left was a phone call between me, the director, and the music supervisor.

The phone call did not go well.

It started innocuously enough. I and our song were repeatedly hailed as “genius” (the adjective, not the noun), and “brilliant.” I understand that this is a revolting thing to say, but I had grown weary of being called those things. Partly because I didn’t believe they were accurate descriptions. Also because it happened a lot. Mostly, though, the reflexive hyperbole of the entertainment business was wearing me down. Everything was either the most incredible thing that could ever happen or a sub-worthless zero. There was no range between them, no middle ground to define them, no sense of proportion, and hence, no meaning. Always a slam dunk, a grand slam, never an easy lay-up, a respectable base hit. The incessant use of the word “genius,” which was just that season’s cultural “boffo,” was offensive. Hadn’t we already lost “awesome” and “literally”? I mean, seriously, genius? Mozart, yes. Dylan, sure. But Harvey Danger? Did people really fall for this? Does anything mean anything anymore?

“Thank you,” I said. “I’m glad you like the song.”

And I was! It was the first or second song we’d written after finishing the album in 1996, and there had been some pressure to add it to the major label re-release of Merrymakers, which we rejected on the grounds of purity. It was essential to us that London/Slash put out the exact same record that Arena Rock had.

We also thought the song might lay a good foundation for a second album, which was, need I restate, the prize our eyes remained trained on. It never actually made the cut. It was, upon reflection, a bit of a Pavement ripoff, which we sort of knew, but we didn’t worry, since it wasn’t exactly intentional.

“Pity and Fear” was a comic title for an imaginary action movie my friends and I had come up with in high school English when we were reading Oedipus the King (which was pronounced there, in Virginia, as “EE-dipus,” a locution I have never encountered since). The song concerned, somewhat elliptically, as was my habit, the months I spent working at the Seattle Weekly in 1995. The first alternative newsweekly in Seattle was founded in 1976, when the city was still a town.

The paper was an important part of that town’s process of forging an identity as an outpost of accessibly eccentric culture among, and indeed infused by, the loggers, airplane builders, and hippie freaks who populated it. It was pre-Microsoft, pre-Starbucks, pre-Forbes Magazine‘s Most Livable City in America cover. But the Weekly was ready for those developments. In a way, it was born to serve the city that arose from them. The people who ran it had the air of academics and wealth inheritors, and liked to imagine their readership as urbane and “aspirational"—a condescending word that stands in for what they really meant: newly rich and gagging to consume. Increasingly, they wrote about expensive restaurants, clothes, gadgets, and lifestyles, things not one person I knew could afford.

I came to the Weekly as a student journalist increasingly obsessed by music and films whose working assumption that writing criticism about those things was the only paying work that might ever become available to me. I was 22. I had never made more than $15,000 in a year, and that was a good year. I walked in to pitch a freelance story about a movie theater that was closing (first freelance pitch I had ever done). The meeting turned into a three-hour interview and I wound up being offered a job as a combination Music Editor, Film Editor, Youth Culture Editor, and all-purpose writer for all sections. Oh, and Calendar Editor (the data entry position they really needed filled, though I didn’t fully grasp this at the time).

It was a half-time position, and hence probationary, but it was salaried and benefitted, both firsts for me. More importantly, it’s not like anyone else was lining up to pay me to write about the things I was interested in. The Weekly’s editors had gotten the message that they needed to hire someone young, and they looked at me like I was the first person under 40 they had ever seen, like in cartoons about people starving on a desert island and one of them turns into a giant turkey leg.

It should give a sense of their overall predicament that they thought I might be a qualified representative of youth culture. It should give a sense of mine that I was happy to act like one.

The paper had been laid low by the arrival of another weekly publication, The Stranger, which was the paper of the Seattle born from the music explosion—though, ironically, most of the people who ran it could not have cared less about rock and roll. The issue was tone.

The Stranger braintrust comprised publisher Tim Keck, who had started The Onion while in college and sold it to the people who eventually made it into the cultural goldmine it is today, Dan Savage, who was then a cross-dressing theater director who happened to write a sex advice column; and a few of their college friends. What they built was less a paper than a stage on which they could mount their absurdist, contrarian burlesque of a paper each week. Sometimes the performance didn’t work, but usually it did, and even when it crashed and burned, it was usually inspired, and always funny. People argued over The Stranger’s quality, its relevance, its consistency, its disregard for journalistic responsibility. But everyone I knew read it. No one ever argued about the Weekly.

In those days, the Weekly was still charging 75 cents per issue, while The Stranger was free. This illustrated the older paper’s fundamental blind spot, which was that while middle-aged Seattleites might be the economic and political engines of the newly minted boomtown, all the important cultural energy was coming from people who were young and hungry, not so much disenfranchised as not-yet-enfranchised, people who weren’t from Seattle, but who had migrated there and changed it. It wasn’t about 75 cents. It was about what makes you think I should pay to read your paper?

Because the prevailing aesthetic of young people tends toward the coarse and vulgar, with no sense of respect for their elders, the elder statesmen and women who ran the Weekly simply turned up their noses at the unclean gate crashers and more or less ignored them. Like punk never happened, as the saying goes. They eventually dropped the cover charge and got a music writer, but the damage was done.

To be fair, it’s not like the editorial staff was senescent; they were just comfortable, and therefore easily mocked. With two exceptions, they appeared generally to be in their 40s and 50s, and every bit as "aspirational” as the audience they aspired to reach. Their leader, Publisher/Editor/Co-founder David Brewster, was fascinating to behold, a man out of time, though it was hard to imagine what time he might have come from. It was impossible to picture him as a young man, or at least as a young man distinguishable from the tweedy, bow-tied swell he presented as when I met him—a type I recognized from the preppy South, but which had no precedent for me in Seattle. Brewster was a Yale man, a former English professor at the UW, and, if his Wikipedia page is to be trusted, is descended from Mayflower passengers. (In the movie, you’d have cast Hume Cronyn, circa Shadow of a Doubt). He ran editorial meetings as though presiding over a salon ripe with intellectual and civic ferment, then assigned cover stories like “The Rise of Bread.”

He was distantly solicitous with me, though he never once approved a story I pitched, and seemed increasingly aware that my ideas about youth culture (if indeed I even had any) weren’t what he’d had in mind. I don’t know if he was thinking of writing a book on the subject, but it seemed that every time I talked to him for more than a few minutes, he found a way to mention Pericles. And he also had a notion of opening a bar modeled on the taverns of ancient Rome. He was a classicist living in modern times, trying to put out a paper about a hypercontemporary city, competing with another paper whose interest in antiquity went back about as far as Welcome Back, Kotter.

He also had impeccable, but inflexible, grammar. I once came upon him and another editor with loupes in their eyes, poring over a contact sheet of basketball photos, looking for one particular Supersonic.

“I think that’s Gary Payton,” the other editor said, pointing.

“Oh,” Brewster replied, looking down. “Is that he?”

I remember his inflection with perfect clarity, nearly 20 years later. On account of his classical affectations, I began thinking of him as a sort of minor key tragic hero—felled by the hubris that allowed him to put out a city paper that refused to acknowledge people younger than, well, he. It was hard not to find him sympathetic, but only until you worked for him for a while. I was at the paper for about six months, until I simultaneously quit and was fired, in an act of suicide by Senior Editor. I walked straight out of her office and called The Stranger, where I would end up working on and off for the next 20 years. I also wrote the lyrics to this song, “Pity and Fear” (you thought I forgot?), needling my old boss with a slightly sharper needle than was necessary, but I had just lost the highest paying job I’d ever had. Besides, I had no reason to think he would ever hear it.

“Pity and Fear”

Remember Pericles: He democratized the city with his mind

A little wisdom never hurt anyone

Tell that to Socrates

Telling the citizens what they needed to hear

But still they fed him Hemlock

Now, the Greeks don’t speak my language

I don’t get the relevance

I am irreverent, I have no reverence

Show me no deference; I’ll do the same for you.CHORUS:

Did you ever know you’re my tragic hero?

You be the pity, I’ll be the fear

And every subscriber will know

what a truly great man you areIn the conference room, he said to me, quote,

“Avoid your generation’s proclivity for irony and negativity,

held so commonly, don’t let me down, son…”

There was a car, the wheels came off it

And I know almost everybody made a profit

Center your gravity, boy: I’m counting on you to be my protégé

Ha ha ha ha ha haCast it off with a wristflip

Your footsteps are filling up

Every time you turn around

See the idols, knock ‘em down

CHORUSSome wear their politics like an aura

Some take it on like a mantle

Some can’t hold a candle

Some touch, some dabble

But not you!

Which brings me back to the phone call. After calling me a brilliant genius several times, the music supervisor started talking in more detail about what she liked in the song. The “tragic hero” line was the thing that clearly grabbed them all the most. I asked if they had caught that the line was a reference to “Wind Beneath My Wings,” and they had not. No matter. Anyway, brilliant, genius, brilliant.

“The only thing for me?” she finally allowed, “is that I almost wish the lyrics had more to do with the characters in the movie, ifthatmakesanysense?”

I genially said the song was a couple of years old, and actually about my old boss at a newspaper.

“Oh, god, no, I KNOW! That’s what’s so genius about it.” Beat. “I just wish there was some way for the lyrics to be more about the characters in the movie, almost?”

I was starting to get the picture.

“Are you saying you’d like me to rewrite the lyrics to the song?”

“Oh my god, no! Sean, I would never, never ask an artist of your caliber to compromise his art. Never!” She paused for emphasis. “I only wish the lyrics were more—how can I say this?—more… reflective of the characters in the film.”

Here is where I started to blow it.

It seemed clear that she wanted me to say something like “let me take a crack at it and see what I can come up with.” But in fact, it wasn’t clear, which is why I kept asking questions. If I had simply said those words, I might be writing a memoir about what it’s like to still be incredibly rich and famous after all these years in show business.

But something in me needed her to acknowledge what she was asking me to do—for no reason other than that I didn’t know. I suspected. I was aware that the artistic orthodoxy has very clear rules about what you’re supposed to be willing to compromise, and what you’re absolutely not allowed to consider compromising, and this was beginning to sound like an exercise right out of the How To Avoid Corporate Interference textbook.

The thing was: I didn’t subscribe to that particular orthodoxy. That song’s only exposure to the world was as the b-side on a limited edition seven-inch vinyl single of “Flagpole” in the UK. I’d have been happy to write songs on commission for filmmakers, or to modify existing songs to suit the purpose of the film. I’d have been thrilled! I feel the same way now.

I had never drawn a distinction between “pure” artists and workers-for-hire, simply because I have been equally moved equally by both. And furthermore, I think purity is a lie and talking about what is or isn’t art is strictly for tourists. The really interesting work happens when people are given constraints. “The absence of obstacles,” said Orson Welles, “is the enemy of art.”

And speaking of Pavement: “Between here and there is better than here or there!”

I’m trying. I’m trying. I’m trying. I’m trying to explain that by the fourth time in as many minutes this woman told me that she didn’t want me to rewrite the lyrics but that her only wish was that the lyrics could SOMEHOW be other than what they currently were, I grew impatient.

A thing about show business, and maybe about life, but definitely about show business: People rarely say what they’re saying. And I had had a lot of that. And on this particular day, I had had enough of it. I suggested writing additional verses that would be about the characters in the film. She again said heavens no, and again repeated her desire for new lyrics. My frustration mounted, as, I can only assume, did theirs. But I was genuinely perplexed.

“Are you sure you don’t want me to just cannibalize the chorus and write new verses about the movie?”

This was followed by a pause that lasted either five seconds or three hours.

“I don’t know if I’d use the word 'cannibalize,’” the music supervisor said. “I might say ‘improve.’” Her tone was indignant. A third voice came on the line.

“You know what? I don’t think this is gonna happen.” A brief flurry of hasty goodbyes and the call was over, as was our chance of having a song in the opening credits of Cruel Inventions. Elapsed time, less than 10 minutes.

Needless to say, my first response was panic. I tried to reason how I could have done everything, or indeed anything, differently. I called the manager. I called the bandmates. I even dashed off a version of the song, replacing the lead vocal with the film-related lyrics they’d been defiantly not asking for, and asked one of our management team to send it to the least unfriendly party who had been on that phone call.

I’m not sure it was sent. I’m not sure it was heard. I am, however, sure it was not in the finished film, which was a medium-sized hit when it was released on March 5, 1999. Two weeks later, we would officially begin production on our second album. By the time it came out, I was made keenly aware of two things: (1) Awkward chats with people vying to give you lots of money had been good problems to have, and (2) They weren’t my problem anymore.

When I subsequently told this story, which I did many, many times, I usually took the role of outraged artist gasping in disbelief about corporate Hollywood’s legendary insensitivity toward creative types. It was an easy card to play—it’s never hard to make yourself sound smarter than people who work for corporations—and nearly always got a bemused, sympathetic laugh from whoever I was talking to.

Not so when I called my stepfather, whose tolerance for the self-satisfied artistic temperament was worn to the nub by 25 years of working in the movie business. His response was not laughter, but disgust. With me. “If you’re saying you didn’t know what you were doing when you used the word ‘cannibalize,’ you’re full of shit,” he said.

He was probably right.

Still, all these years later, I believe it was the correct word to use, on several levels—just not the level where you get paid $100,000 to have your stupid song in a stupid movie. Had I not been in a situation in my life for the first and only time in which it felt more important to say “cannibalize” to a music supervisor than to make a lot of money and gain a lot of exposure, I might have made a different choice. All things being equal, I should’ve just pretended my cell phone had entered a bad zone.

Which it obviously had.

Post-script: The title of the film was changed before release from Cruel Inventions to Cruel Intentions in response to the fear that moviegoers might believe the film to be about scientists. The opening titles were scored by “Bittersweet Symphony” by the Verve, whose lyrics, presumably, apply to all of us. “Try to make ends meet. You’re a slave to money then you die,” indeed.

A propos of money: In 1997, roughly a year before this whole fiasco unfolded, David Brewster and his partners sold Seattle Weekly for over $30 million.

Now who’s a tragic hero?

(Released in 2025 as a PDF with the KJV bonus material.)