At the risk of sounding foreword…

“So, who here can tell me what the difference is between poetry and prose? Can anyone tell me? Well—er—poetry comes in those short little lines! Isn’t that the difference? Well, all right—all right, let’s say it is. But can you tell me, then, how the length of the lines could possibly affect the way the words convey meaning? Do the words care what size of line they’re on? But all the same, this indefinable difference has had some very definable results in my life over the years, in my opinion.”

— from The Designated Mourner, Wallace Shawn

Every time a songwriter, even a great one, refers to her work as “poetry” I detect a private cringe in that part of my psyche that can still accommodate the narcissism of the small distinction. It’s bad enough we get stuck with a damp word like “lyrics.” A song is not a poem. I can’t tell you why, exactly (not if we want to get this fucker off to the printer in time) so I will settle for the explanation offered with typical bluntness by Robert Christgau in 1967: “Poems are read or said. Songs are sung.” A+. I might elaborate that poems have their own internal music that can be heard or felt by the reader or sayer. More Christgau: “However inoffensive ‘The ghost of electricity howls in the bones of her face’ sounds on vinyl, it is silly without the music.” I might not go as far as “inoffensive” or “silly,” but I can’t deny songs need a piano, a guitar, a bass, a drums—rhythm to propel them and melody to lift them.

These songs do, anyway.

Without their external music, these songs are words minus context. What the page can’t show is how each line responds to developments in the song’s chord structure, rhythm, dynamics. (Though I am willing to stipulate that if you are one of the savvy few flipping through this demure folio, it’s likely you’ll be able to hear each bar of that absent music in your head as you read; your custom is cherished.) Even if they seem to, words don’t make sense without musical accompaniment—or at best, they make as much sense as a single shoe lying on a sidewalk next to a cardboard sign that reads “Free.” Absent a partner shoe to define its interdependence, a foot to fill it up and give it purpose, or even so much as a lace to pull it together, this lonely shoe is a curio for the curious, and not a proper book for reading and certainly not poetry.

Disclaimers thus disclaimed, this subnumerary shoe is also, at this precarious moment (age: 36, vital statistics: farcical), the only thing I could credibly call my life’s work. Putting these words to these songs is the project I have worked hardest on, and put the most of myself into, at all, ever. Full stop. End of. This project has determined my course, whether I was running towards or away from it, for 15 years. During which time everything in my life changed and changed again, except this. These songs are not just the stick I use to measure my worth; they are also the bricks I have used to construct a self. The words arise from notions of identity, ideology, conviction, impersonation, silliness, and solemnity—elements I’ve self-consciously tried on in an effort to be a person, the way other people seem to be people without even having to try. I remember thinking once that I was especially happy to have written “Old Hat” not simply because I meant it, which I did, but because in order to sing that song I knew I had to be the kind of person who could. I used to joke that I only had four kinds of songs: girlfriend, family, culture, self. Then I realized: it’s not a joke. That’s everything I’m interested in. What I’m ëposed to write about, cars? Milkshakes cold and long? The road? When we started, all I had to do was cram some words, any words, into the music. My qualification was wanting to. And I did want to. No one was listening, and even if they had been, they wouldn’t have heard much because I was singing into a guitar amp (comma not a very good one). Funny how that lark blossomed into aspiration into ambition into discipline into a bag of tricks, and then, at long last, a voice I could recognize as my actual own.

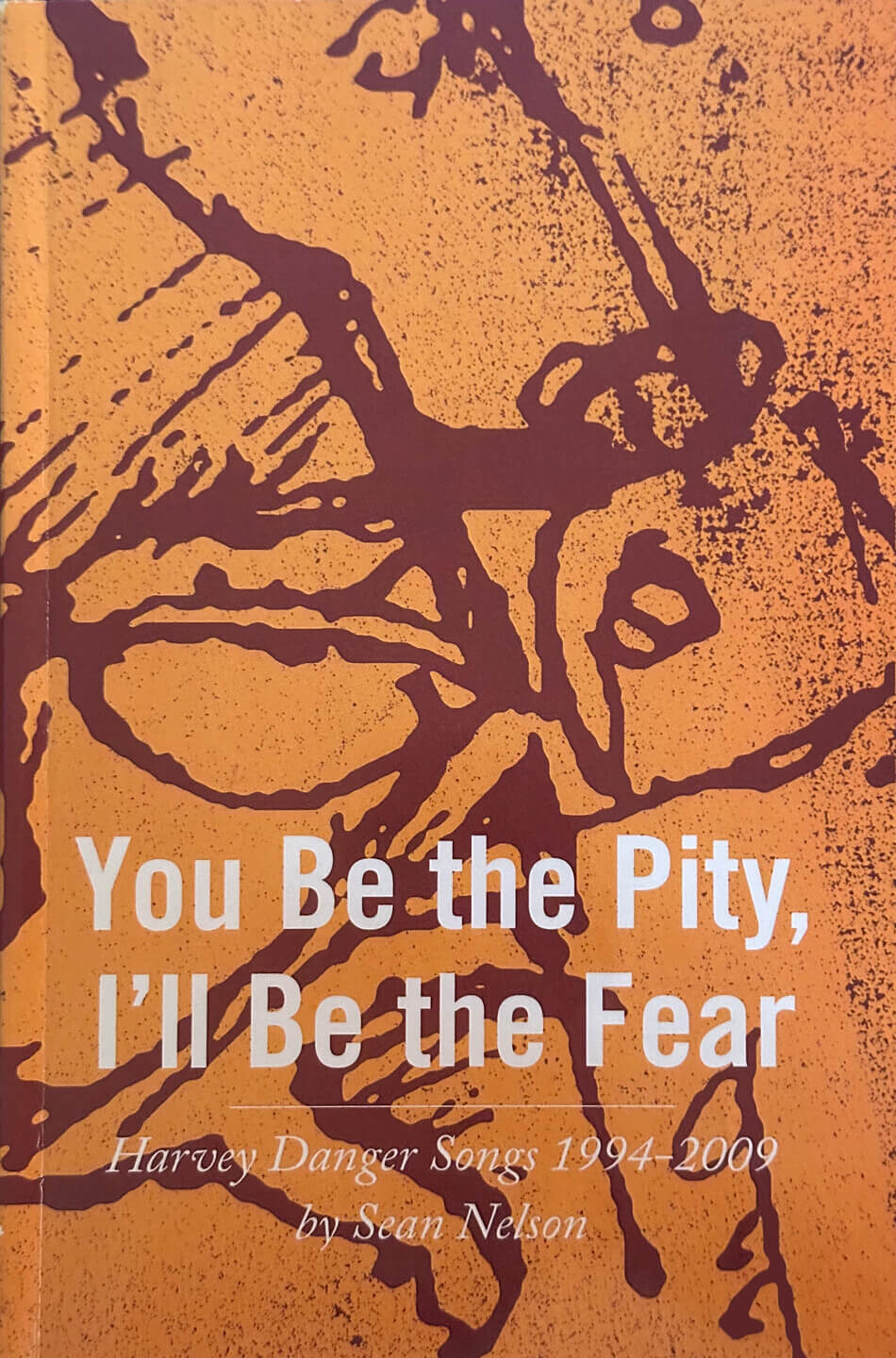

So, this book does not contain poetry. It’s not even a proper book. It’s a free shoe. It’s my free shoe. Thank you for caring about my free shoe. I wish I had more songs to collect here. My co-writers and I were never terribly prolific. I used to think that was because we had such high standards, but that’s just what people tell themselves when they don’t want to work harder. To see all these lines in one place is not only to collapse time but to condense all the selves I struggled to be by writing them. I remember every circumstance of every song with creepy clarity; every choice, no matter how right or wrong I feel it is now, lives in me every time I hear or even think about these verses and choruses. And bridges! Lots of times I see the influences of other writers, songwriters, and friends more clearly than I can hear myself. Even divorced from their recordings, the songs remain a second-guess minefield. I wish I had finished “Problems and Bigger Ones,” “Terminal Annex,” and “My Human Interactions.” I wish I’d thought to change that one line on “Pike St.” (I changed it here; it’s my book!) Wish I hadn’t been so petulant all over King James Version. Wish I’d tried one notch harder all over the place. And yet. “Big Wide Empty,” “Defrocked,” “War Buddies,” “Little Round Mirrors,” “Moral Centralia,” “Cold Snap,” “Jack the Lion,” “Wrecking Ball,” “Radio Silence,” others. I couldn’t say them any better. I still can’t. Even without the music, they reveal what they’re trying to reveal. At least I hope they do. Not that I’m saying they’re poetry, you understand. I’m just pleased to see them here, perfect bound and ready to be read and said, or even sung. Anything more is just, as the poet reminds us, gravy.

Fifteen years from now I will be 51. I have no idea where I will be or what I will be doing. I do know this: I hope to have another 40 or so songs I can collect in a book like this. Or more, even. Lots more.

— Sean Nelson

August, 2009

Seattle